Are You Using Learning as Punishment?

Art history, research, reading, and writing should not be a punishment.

I get it. It’s REALLY hard and frustrating when students aren’t taking care of art materials. But when the punishment is to take away materials and hand them information about artists, that sends the wrong message.

Art history can and should be fun and exciting. Punishing by trying to make students miserable or bored doesn’t address the issue and causes further damage.

Learning shouldn’t be a punishment. When students are destructive, disinterested, and disrespectful, often the solution is to assign them a research project, reading, or writing assignment. While I understand that when students are destroying materials and property, you can’t continue handing them new materials to ruin, assigning them work deemed boring or extremely hard isn’t the solution.

This type of assignment sends the wrong message. It tells students who aren’t convinced that education matters that education not only doesn’t matter, it’s a punishment.

Assigning students work that they don’t connect to or understand often leads to further misbehavior or even more disengagement that can be hard to come back from.

What is the real problem when students destroy or disrespect people, property, and supplies? How do we address the issue before it starts?

The book Upstream by Dan Heath talks about noticing a problem and, instead of addressing the same issue repeatedly, trying to understand the cause so that you can, more often than not, stop it before it happens.

“In 1998, the graduation rate in the Chicago Public Schools was 52.4%. A public-school student in Chicago had a coin flip’s chance of getting a high school degree. “Every system is perfectly designed to get the results it gets,” wrote the health care expert Paul Batalden. And CPS was a system designed to fail half its kids.” p 23

Upstream by Dan Heath

Chicago Public Schools reviewed data and realized that with 80% accuracy, they could predict if a student would graduate based on a few key indicators tracked during their 9th-grade year. Over four years, the graduation rate rose to 78%.

Chicago Public Schools found success because they addressed the problem before it happened and addressed it at a systems level. I want to clarify that I do not believe teachers can or should address behavior problems alone.

Recently, I heard from a teacher working with a student struggling with reading who didn’t want to practice. (This should come as no surprise. Do you like to do things that you aren’t good at?) The teacher knows that intervention needs to happen now, or the student will encounter more significant hurdles in the coming years. When kids (and let’s be honest, adults too) feel overwhelmed or like the task in front of them is too hard, they tend to act out. That might look like yelling, throwing things, or shutting down and refusing to do ANYTHING!

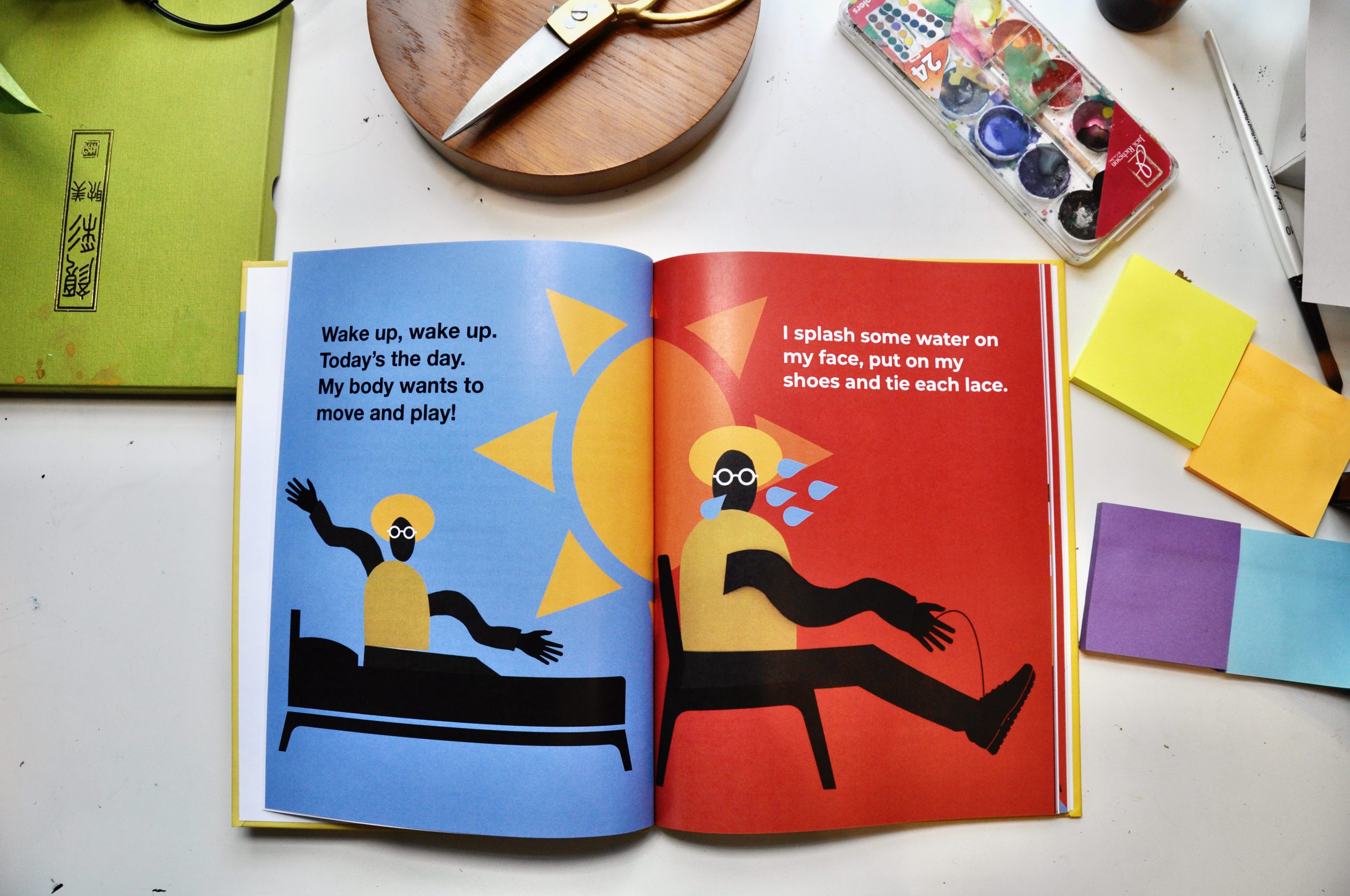

Instead of feeding into the student’s anger and frustration or creating a punishment through a different learning activity, the teacher started doing jumping jacks. (That’s not what you thought I would say, right)?

It caught the student off guard as well and, therefore, caused them to laugh. Next, the teacher encouraged the student to join in the jumping jacks. A few movements later, the student was back working on reading practice.

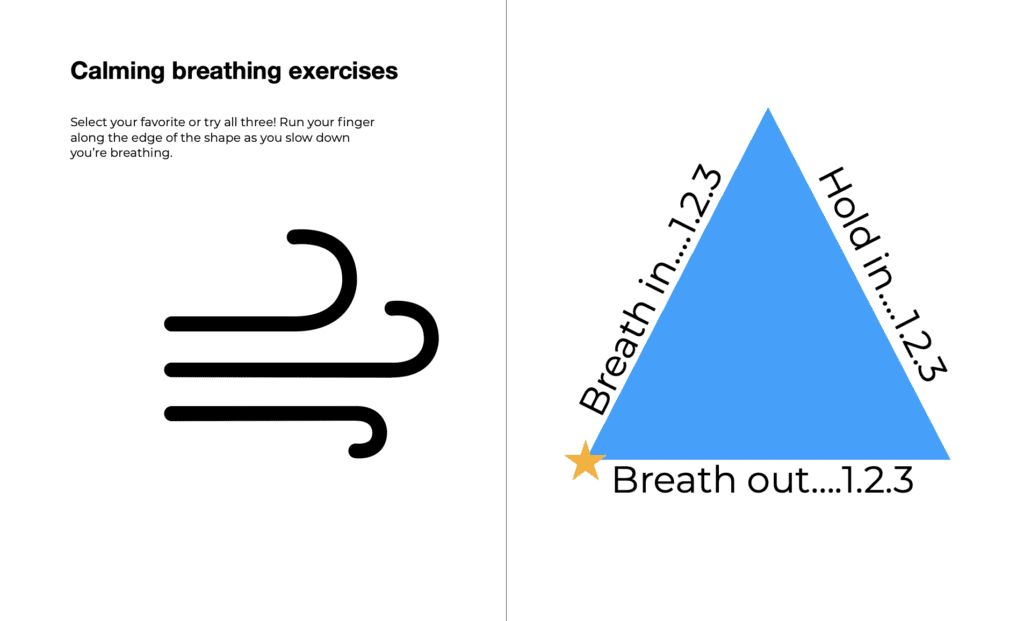

Moving our bodies makes us feel better; it helps to clear our minds and get our heart pumping. Too often, we forget about the importance and the power of movement in the classroom.

If you have a class you know is rarely engaged, try starting the class with some movement, don’t wait for things to go wrong. Provide students with tools and support to process their frustration safely and respectfully.